Reverse logistics—the process of returning goods to sellers or manufacturers for resale or disposal—is already a complicated business. But things are about to get worse, according to transportation and logistics experts who warn that a supply chain already in crisis is unprepared for a coming surge in holiday returns.

“With the buying trends that we have out there, both on the B2B side and the B2C side, I don’t think we’re prepared for it,” says George Swartz, vice president and the distribution and logistics transformation practice lead at CapGemini Invent. “COVID accelerated this, but we’re already headed down this path where we’ve gotten into the habit of ordering everything that we think we might be, whether its size, color, specification, technical piece, whatever and keep only one and send the rest back.”

“You’re already looking at a transportation shortage. We’re looking at a huge uptick over the last three to four years in LTL [less-than-truckload] small parcel package last-mile kind of deliveries which has really stressed that system. Reverse logistics just stresses it more because it’s more packages into the market,” Swartz says.

The American Trucking Association estimates that transportation providers need about 80,000 more drivers to meet existing demand. That shortage could double by 2030, ATA estimates.

Optimize and reduce

To cut the costs of reverse logistics, retailers can optimize their shipping and warehousing operations, or take steps to reduce the number of returns that need processing. 1822 Denim, which sells apparel on its own website, in marketplaces and through partnerships with retailers such as Nordstrom, took the latter approach. And it worked.

The manufacturer says it reduced returns by 40% after rolling out a sizing app to help ensure shoppers didn’t need to make a return.

1822 Denim partnered with 3DLook, which makes apps to help shoppers with sizing and fit. The virtual try-on feature in a 3DLook app takes measurements in three dimensions, recommends a size and lets shoppers see how something looks before they buy. That reduces a shopper’s need to “bracket,” i.e., purchase several of the same items in assorted sizes to try on at home—and then return the ones that don’t fit.

1822 Denim uses a sizing app from 3DLOOK that lets shoppers see how well an item will fit.

That drop in returns turned into a marketing opportunity, according to Tanya Zrebiec, vice president of innovation and strategy for 1822 Denim. 1822 makes sure shoppers know they’re reducing the environmental impact of reverse logistics, when they use the app and get the right fit, Zrebiec says.

“We do quite a bit of marketing around how it reduces your carbon footprint and all of that good stuff,” she says, noting that the company’s website tells customers the 3DLOOK app “greatly reduces the number of returns. Less returns means a healthier planet by reducing waste in landfills, and decreasing a trail of emissions that contributes to climate change.”

“I really do believe that fashion companies and clothing companies can really tap into, you know, human connection and be able to spread the word and say ‘Hey, you really need to help the planet more and these are the ways you can do it’ other than putting all of the expectation on the brands to do all the work. They need to also be a part of helping clean up the planet, right?”

Product description pages

David Morin, senior director of retail and client strategy at Narvar, which provides a returns and customer-loyalty platform to retailers, sees a way to reduce returns by tweaking one of the core marketing components in ecommerce: the product description page.

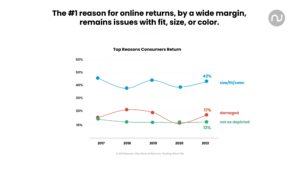

Fit, size and color are the top drivers of returns in ecommerce, according to Narvar.

“One really common return reason that we see across the industry is something like ‘not as pictured’ or ‘not as expected.,'” Morin says. “We’ve worked with so many retailers who all we had to do was go look at the website, and the picture looks pink and the description was more orange, and we can work with our UX team to make the description and the color better match.”

Similarly, “a retailer might see a particular SKU is being returned overwhelmingly ‘for size too big,'” Morin says. “And what we’ve seen is oftentimes a retailer will then update their PDP and say, ‘Hey, 60% of people who returned this say it’s because it’s too large, we recommend that you downsize by half a size.'”

Returns could hit $120 billion

Optoro, which provides reverse logistics services to retailers, forecasts that U.S consumers will return $120 billion worth of goods between Thanksgiving and the end of January 2022. That’s well above the $115 billion Optoro forecast for the holiday season last year. The National Retail Federation has not released its returns forecast for 2021 as of press time. The NRF estimated the cost of returns for the holiday season of 2020 was $101 billion.

And refunds to consumers are just one of the costs that retailers incur from returns, CapGemini Invent’s Swartz says.

“The other thing that’s really difficult is the processing on the back end. Once I receive the goods, I’ve got to inspect them, I potentially have to repackage them. And I’ve got to get some of them back on the shelf. That all takes labor and I barely have enough labor to get fulfillment done now, let alone get all this inbound processing and all this inspection,” Swartz says.

Lots of third party, reverse logistics providers are available to help with the load, but Swartz notes that “they’re having trouble finding labor as well.”

The environment pays a price for reverse logistics too. Returned inventory creates 5.8 billion pounds of landfill waste each year, according to research by Optoro and Environmental Capital Group, while trucking those returns back to warehouses, stores or landfills emits over 16 million metric tons of carbon dioxide each year.

No quick fixes

CapGemini Invent’s’ Swartz says retailers’ struggles with reverse logistics aren’t going away any time soon. There seems to be far less emphasis on optimizing reverse logistics than there is in streamlining inventory procurement and delivery to customers, he says.

Any of the tracking and tracing systems in use in retail can be adapted to reverse logistics, but retailers don’t feel the need to commit resources to improve the process. “There’s not a sense of urgency that I have to expedite it to bring it back in. I’m not even as worried about tracking it through the process, other than making sure the customer gets his money back,” Swartz says.

And any attempt to improve the system will need to find a way around the labor shortage in warehousing and transportation. “On the material handling side, we need to figure out what automation solutions can help with that because you’re still having the labor problem which isn’t going away,” Swartz says.

Favorite